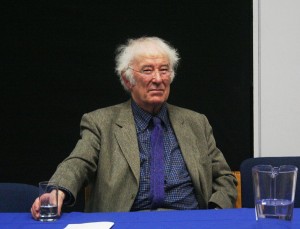

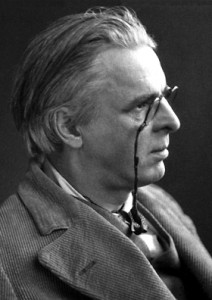

This weekend it’s been hard to avoid comparisons between Seamus Heaney (who sadly died on Friday) and WB Yeats. Both were Irish poets who won the Nobel Prize for Literature; both were well-known beyond the autolytic world of contemporary poetry; and both cast a long shadow over the writers who came after them.

(photo credit: Sean O’Connor)

Watching Friday’s evening news I remembered a less obvious addition to the list: both were disproportionately famous for one or two early poems, even though their best work came later. In a radio broadcast in the mid-1930s Yeats described “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” as “the only poem of mine that is very widely known”. By then in his seventies, Yeats had written the poem almost fifty years earlier – and in the decades between had crafted some of the greatest poetry in the language. This is perhaps inevitable in the rare cases where poets become household names: while the tiny minority who read contemporary poetry were reeling from their first encounters with The Tower and The Winding Stair, the wider public’s version of Yeats still began (and for decades would continue to begin) “I will arise and go now”.

Similarly, the 6 o’clock news (and pretty much every other TV and radio station) gave us footage of Heaney reading “Digging”. With the exception of Bill Clinton’s favourite lines from The Cure at Troy (“It means once in a lifetime / That justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme”), all of the poems that night came from Heaney’s first collection, Death of a Naturalist.

It would be easy (and eye-wateringly crass) to get sniffy about this. Those of us who’ve spent hours studying the dimeters in part II of “The Tollund Man” to learn how the trick is done may cherish the Heaney of Wintering Out, North and Station Island, but tens of millions have known:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

It doesn’t diminish Heaney’s achievement (quite the reverse) to acknowledge the part that being on the syllabus played in his success. For many people, the only poems they ever read are the ones they read in school, and for anyone in the UK or Ireland who went to school since the ’80s that meant Heaney. “Digging” didn’t make the evening news because some BBC editor weighed it up against “Exposure” and decided it was a better fit, but because there’s a reasonable chance that the editor (and somewhere north of thirty million others) remembered the poem from school.

Not just studied, but remembered. Heaney’s poems stick in the mind years later when much of what we slogged through at school has faded. What better argument can there be for putting real, first-rate contemporary poems in the classroom?

But like Yeats, there’s a lot more to Heaney than the poems everyone knows. So if you’re one of those thirty-odd million who remember “Digging” and “Follower” but have never ventured further into his work, what better way to remember that generous, humble and gifted man than to get hold of a copy of North or Station Island and to spend some time with one of the great poets of our time?

So please head to the library or bookshop and pick up some Heaney. Then find a quiet corner and read it, slowly.

This goes double if you’re any kind of writer: poems like “Sandstone Keepsake”, “The Underground”, “North” and “The Tollund Man” don’t just teach us to see the world in new ways; they teach us how to write better poems.

In “The Master” Heaney deals explicitly with the influence of Yeats. An apprentice poet visits the master (“like a rook in an unroofed tower”) only to discover that “his book of withholding” contained “nothing / arcane, just the old rules / we all had inscribed on our slates”. As Yeats was to Heaney, so Heaney has become for so many contemporary poets:

How flimsy I felt climbing down

the unrailed stairs on the wall,

hearing the purpose and venture

in a wingflap above me.